Prevalence of myopia in Swedish school kids

Pelsin Demir

Introduction

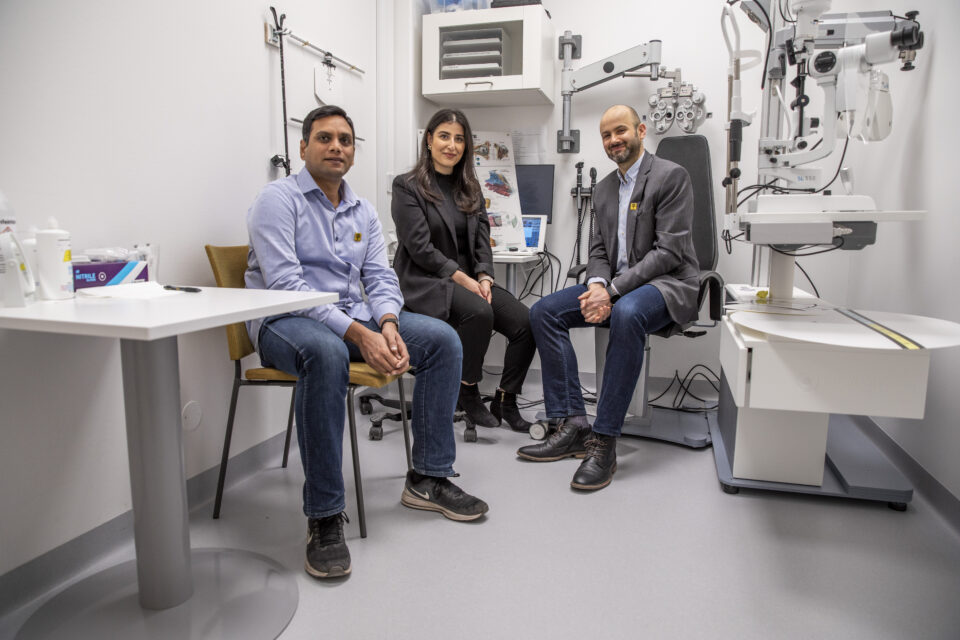

Pelsin Demir has just finished her PhD after four years of intense work. She initially chose the topic of myopia because – as she says – we still need to learn the theory and find the causes behind it.

Together with her team, Pelsin did one of the first comprehensive studies of the prevalence and development of myopia in Swedish school kids. She reached some valuable conclusions for optometrists working with myopic patients daily.

In this interview, we delve into her work and ask what it has meant for her career to do a PhD. Pelsin is passionate about the topic and underlines how we need much more research in the field. She also shares why the findings were quite surprising and somewhat nuanced the common notion of myopia being a future global pandemic.

- Q1 What has the PhD meant for your professional development?

- Q2 Why did you choose myopia as your main topic?

- Q3 How did you go about that?

- Q4 What did you find out in your first paper?

- Q5 Did you discover an increase in the overall prevalence of myopia?

- Q6 You also examined different types of refractors?

- Q7 What was the topic of the third paper?

- Q8 What are three essential takeaways for optometrists who see myopic children regularly?

- Q9 Is there anything else to be aware of?

- Q10 What is your opinion of the current development of myopia studies in general?

First: What has the PhD meant for your professional development?

It was one of my dreams to do a PhD one day! Now, I can work academically and teach students, which has opened many doors for me. I will continue working at Linnaeus University and give lectures on myopia. They also have a clinic where you can see patients on a running basis.

The PhD helped push me outside of my comfort zone. Because suddenly, I was an expert who did talks on the subject on, for example, Viewpoint, where I authored a complete handbook.

Myopia knowledge always stayed on top of my mind. I never knew when another presentation, article, or lecture would come up. I still remember the first time I had to talk in front of an audience. It was in Gothenburg six months after starting my research, and I was so nervous. But every time, it just got better and better.

Why did you choose myopia as your main topic?

Because it was a hot topic, and there is still so much to explore.

Already in my undergraduate programme, I did a project on myopia and near work among children from age 8 to 19. Using an autorefractor measuring refractive error, I travelled to different schools and tested 500 students.

In 2016, I won a travel grant to ARVO, the biggest eye conference in the world. Each day you have a new topic there, and on the day of myopia, it crossed my mind that there were very few representatives from Sweden or Scandinavia.

I read up on it and found that the latest paper on myopia amongst Swedish children was from 2000. And another report concludes that in 2050, half of the world’s population will be myopic. But we had minimal updated research on the situation in Sweden.

So, I had to fill that gap.

How did you go about that?

I was fortunate to receive total funding. Specsavers financed two-thirds of my PhD, and Linnaeus University’s Faculty of Health and Life Sciences gave the rest. In my contract, I had five years to do the PhD and teaching, but I was fast and did it all in four years.

My key objective was to discover the prevalence and incidence of myopia in Swedish school children. We had a cohort of 128 students aged 8-16 years at baseline and followed them over 24 months with regular visits.

We assessed changes in their eyes and studied selected behavioural aspects: How much time were they spending outdoors? Were they looking a lot at their phone screens? At what distance? And we also looked at heritage, parental myopia, and ethnicity.

The result was four different papers with each their conclusions.

Let's delve into them. What did you find out in the first one?

The first paper was about prevalence and baseline characteristics – i.e. the associated risk factors for myopia.

We found that 10 per cent of the children were myopic the first time they visited us. The majority were hyperopic. Children with one or two myopic parents had both longer axial length and a more negative refraction. So, parental refractive error conditions turned out to be the most consistent factor associated with myopia in the kids.

Surprisingly, we could not find any association with near work. But children who spent more time outdoors had a shorter axial length. That shows how outdoor time is indeed protecting the eye from becoming myopic.

And how about the overall prevalence? Did you discover an increase?

We described that in our fourth paper.

The annual incidence rate was 3.2 cases per 100 persons, which is very low compared to, for instance, East Asia. We could see that the parental history and the type of refractive error (ametropia) at baseline significantly influenced myopia development and progression. Myopes had a faster progression towards negative refraction than hyperopes.

It was a surprise that we did not see a higher myopia incidence, which would support the global pandemic warning. Looking back at the study from 2000, it investigated 1000 children in Gothenburg and found that approximately 50% of them were myopic.

The results calmed us down, and the high number from the previous Swedish study can be explained by the different methodology they used. But we are still looking at reasons for myopia development, such as lifestyle and genetics.

You also examined different types of refractors?

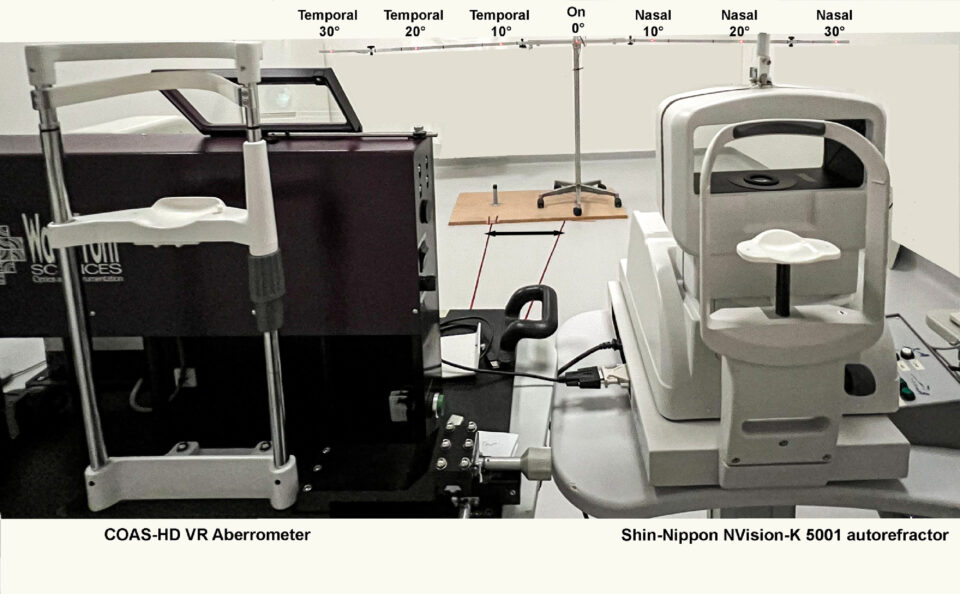

Yes. We used two types of refractors to investigate refractive errors: Shin-Nippon open-view autorefractor and COAS-HD VR open-view aberrometer. We wanted to find out whether they gave the same results or not when comparing central and peripheral refraction in children.

It turned out that the Shin-Nippon autorefractor measured more hyperopic than the COAS-HD VR aberrometer. So, you need to take caution when comparing results from instruments with different measurement principles.

However, both work well when it comes to measuring peripheral refractive error. That was the topic of our second paper.

That takes us to the third paper. What was its topic?

The third paper explored structural and microvascular measures of the fovea in the eyes of healthy children.

Previously, we thought that the foveal area was avascular in healthy eyes and that blood vessels would only be found in, for instance, premature children.

But here, we found that children born full-term and with visual acuity in the normal range can still have microvasculature in the centre of the fovea. So, it seems there is a natural variability of the foveal vascularisation in children.

This discovery opens up a lot of new research to be done…

What are three essential takeaways for optometrists who see myopic children regularly?

- Always recommend more outdoor time. (It is still the most evidence-based management for protecting the eye from developing myopia).

- Do not automatically assume that a child is premature, just because you find microvasculature in the foveal area when taking an OCT scan.

- Look at parental history, as it plays a very important role in myopic development in children.

And I’ll add a fourth one, too:

Be aware that in the future, it looks like we will measure not only central refractive error but also peripheral refractive error.

Is there anything else to be aware of?

Yes! Even though the prevalence was low in our sample, there was still a fair percentage of myopes that optometrists need to manage. And it is vital to remember that nowadays, children get myopic at a younger age. The younger they are when developing myopia, the higher their risk of developing pathological changes in the eye.

Consequently, we must start examinations at a younger age – preferably before six – and follow up. The eye is hyperopic at birth. The process of emmetropization takes place throughout childhood. If there is a disruption to this process, we have a refractive error.

This growth mechanism continues into early adult life, so clinicians have a large window of opportunity to make a difference in a person’s refractive error development early on.

In other words: school-age is a critical period to examine for myopia.

Last, what is your opinion of the current development of myopia studies in general?

In the past two decades, it has exploded with myopia studies, new interventions, and instruments. But we still don’t know the causes of the condition. Neither how to cure it nor stop its progression.

Researchers are still turning everything upside down on myopia. When I started doing my PhD, it was all about myopia and choroidal thickness. Now, the focus is on outdoor time and school pressure.

The condition remains a mystery, and there is still so much we need to find out.