Classification by degree

Classifying myopia by degree is the most common way of classification, and most likely, the one you use at your practice daily. The consideration of myopia sometimes differs when reading studies or literature. For instance, some studies consider a patient as myopic when their refractive error is -0.50 D or more, but others may define their patient as myopic when their refractive error is -0.75 D or more. The difference may be due to the age of the patient or the methodology of the examination. If the patient is a child and undergoes cycloplegic refraction, studies usually define myopia as -0.50 D or more. However, if the patient is a child but doesn’t undergo cycloplegic refraction, studies usually define myopia as -0.75 D or more. The reason some studies increase the definition of myopia is to eliminate artificial myopes with uncontrolled accommodation.

At this point, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), the criteria for myopia is -0.50 D or worse. This means that as soon as a patient has -0.50 D or worse, they’re considered myopic and classified in the ‘low myopia’ category. Subsequently, if the refractive error is between -2.00 D to -5.00 D, it’s classified as ‘mild myopia’, and if it’s -5.00 D or worse, it’s classified as ‘high myopia’. In earlier days, high myopia has been classified as myopia worse than -5.00, -6.00, or even -8.00 D. The reason that -5.00 D is now considered as high myopia is because the risk of complications increases significantly at this level. Also, an uncorrected myope with a refractive error of -5.00 D meets the WHO blindness criteria. Therefore, I would recommend these categories if you want to classify myopia by degree.

- Low myopia: -0,50 D to −2,00 D

- Mild myopia: -2,00 D to -5,00 D

- High myopia: −5.00 D or more

Classification by age of onset

Another way of classifying myopia is by age of onset. Here we can distinguish four categories:

- Congenital myopia (present at birth and persisting through infancy)

- Youth-onset myopia (< 20 years of age)

- Early adult-onset myopia (20-40 years of age)

- Late adult-onset myopia (>40 years of age)

Classification by clinical entity

Last but not least, we have classification of myopia by clinical entity. I’ll describe them one by one.

Congenital myopia

Congenital myopia is present since birth, and the patient is usually diagnosed at 2-3 years of age. We see this more frequently in children who were born prematurely or with various birth defects. The refractive error is about -8.00 D to -10.00 D and remains constant. Congenital myopia can sometimes be associated with conditions such as cataract, microphthalmos, aniridia, and megalocornea. If it’s is unilateral, the patient may develop amblyopia, which can lead to strabismus. If congenital myopia is bilateral, the patient may have difficulties with distant vision and holding objects very close. It’s best if congenital myopia is corrected early, to help children develop normal distance vision and perception of the world. The child will undergo retinoscopy under full cycloplegia and prescribed with full correction.

Simple myopia

Simple myopia, also named physiological or school myopia, is due to a physiological error and isn’t associated with any eye diseases. The clinical picture of simple myopia is rarely present at birth, and the patient is born hyperopic and becomes myopic at the age of 7 to 10 years. The progression of myopia stabilises around the mid-teens, and the patient usually reaches a refractive error of around -5.00 D and never exceeds -8.00 D. The reason for developing simple myopia is often because of spending many hours looking at close distance and spending too little time outdoors.

Late-onset myopia

Patients with late-onset myopia are typically adults of 20 to 40 years of age, mostly students or workers who spend a lot of time in front of screens without taking any breaks. Their myopia develops slowly. A combination of accommodative anomalies, many near activities, and too little daylight may cause late-onset myopia.

Nocturnal myopia

Nocturnal myopia or night myopia occurs only under conditions of dim illumination or darkness and primarily appears due to a combination of increased accommodative response and low levels of light. In the dark, both insufficient contrast and increased spherical aberrations result in an inadequate accommodative stimulus. So, the eyes don’t focus on infinity but assume the intermediate dark focus for an accommodative position. The main symptom of nocturnal myopia is blurred distance vision in dim illumination. Patients may complain of difficulty seeing road signs when driving at night.

Pseudo-myopia

Pseudo-myopia, also called artificial myopia, occurs due to an accommodative disorder. The patient has an excessive accommodation and spasm of accommodation. Be careful with pseudo-myopic patients! They can really fool you, and you need to be attentive. Pseudo-myopia is generally encountered in younger emmetropes or slightly hyperopes who spend much time doing near work or activities. The patient complains about blurry vision at far distances that’s transient but greater, especially after near activities. This is what happens: when the patient is viewing near for a longer time, without taking any breaks, it causes hypertonicity of the ciliary body of the eye. Therefore, an emmetropic or slightly hyperopic patient may clinically appear to be myopic. If the patient is myopic, it may still seem to be more than it already is.

So, now you may wonder: what do I do with a pseudo-myopic patient? Or how can I identify them? Well, in most of the cases, the autorefractor gives you a high negative refractive error value such as -6.00 D or -7.00 D, and you think: “oh, this is a high myope”. You take the patient’s history, and he or she says: “This is the first time I will undergo an eye examination. I just started a new job with a lot of screen time, or I study all day, and I can’t see at far distances at the end of the day. It gets clear after a while, but this repeats itself every day”. Then you measure their visual acuity, and they see 20/20, which doesn’t make any sense, right? These are all red flags! What you have to do now is relaxing the patient’s accommodation, either with cycloplegia or letting the patient wear trial frames with at least +2.00 D for approximately 40 minutes. After that, you perform a refraction and always prescribe plus lenses.

Induced myopia

The natural history of induced myopia depends on the initiating condition or agent. A refractive shift towards myopia after the age of 60 is usually associated with the development of nuclear sclerosis of the crystalline lens – therefore, it’s a form of induced myopia. Induced myopia is often temporary and reversible. Variability in blood sugar levels may also cause induced myopia. It’s essential that you ask questions about the patient’s blood sugar level and whether this is stable. High blood sugar levels may show a more myopic refractive error, and low blood sugar levels may give a more hyperopic refractive error. Patients with induced myopia also report blurred distance vision. The time course of the distance blur depends on the agent or condition that has induced myopia. Whether other symptoms are present depends on the cause of the induced myopia.

Degenerative myopia

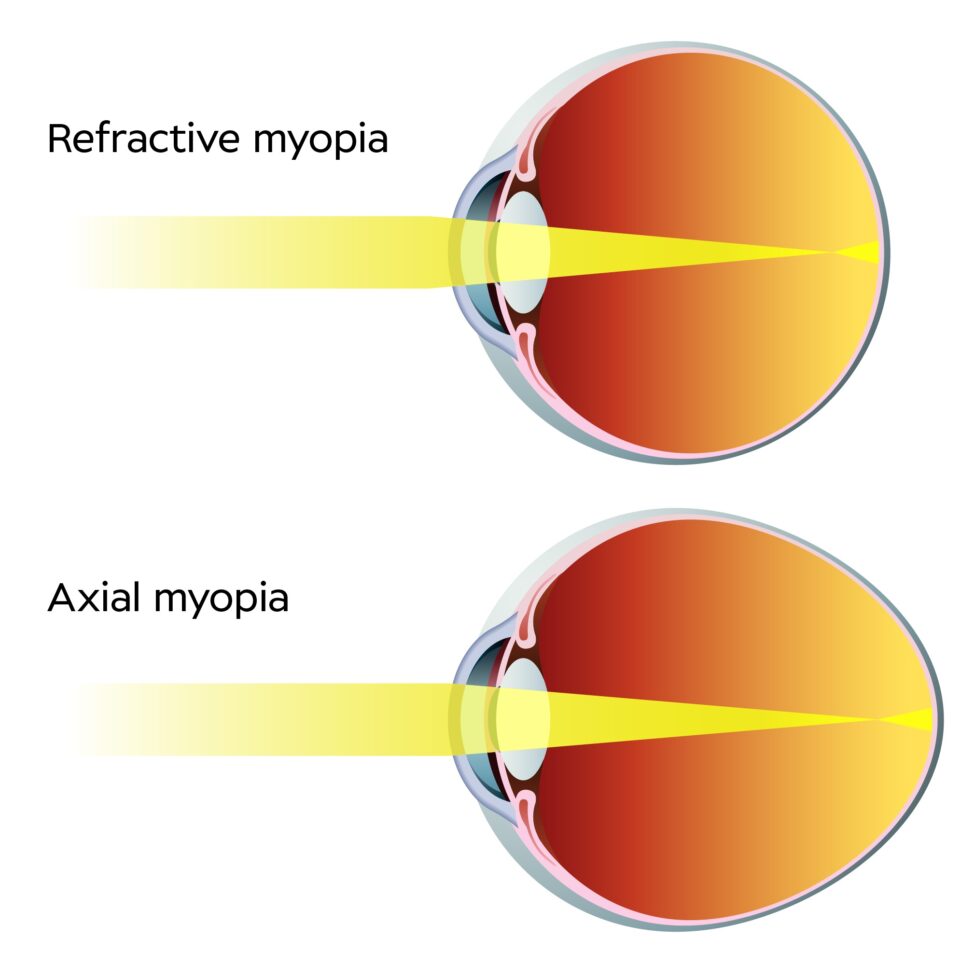

Degenerative myopia appears because of the rapid growth of the axial length, which grows outside the normal biological variations of development. This rapid development may also be associated with pathological changes in the eye. Elongation of the eye causes stretching of the retina and the tissue behind the retina. We see this as a tessellated appearance in fundus pictures and increased visibility of the choroidal vasculature. The peripheral retina gets affected as well and produces characteristic changes of degenerative myopia.

If a patient has degenerative myopia, they have to hold near-point objects quite close to the eyes due to the magnitude of uncorrected myopia. The patient may notice flashes of light or floaters associated with vitreoretinal changes. If pathological posterior segment changes have affected the retinal function, the patient may have a history of vision loss and, perhaps, uses low-vision services or devices. The refractive error increases by as much as 4.00 D yearly and stabilises at about 20 years of age. Occasionally, it may progress until the mid-30s and frequently result in myopia of -10.00 D to -20.00 D. Patients with degenerative myopia may also express concern about the high power of their optical correction. They often have some discomfort due to the weight or inconvenience of the correction. Severe congenital myopia during infancy or high myopia typically becomes degenerative myopia.