Uveitis is defined as inflammation of the uveal tract, which is further subdivided into anterior (iris and ciliary body) and posterior components (choroid). The inflammation may affect surrounding tissue like the retina and optic nerve.1 Uveitis, particularly posterior uveitis, is a common cause of preventable blindness, deemed a sight-threatening condition. It is responsible for between 10% and 15% of all cases of blindness and 30,000 new cases of legal blindness annually in the United States.(2,3) In Western countries, uveitis affects 200 per 100 000 people.(4) More than 35% of patients who develop the condition suffer severe visual impairment.(4,5)

The classification of uveitis is based on anatomical location and is as follows:

| Type of uveitis | Primary location |

| Anterior | Iris, ciliary body, or both |

| Intermediate uveitis | Vitreous |

| Posterior uveitis | Choroid |

| Panuveitis | The entire uveal tract and vitreous |

Furthermore, uveitis is – additionally classified – by the following characteristics:(6)

- Onset (sudden vs insidious)

- Duration (limited, < 3 months in duration; persistent, >3 months in duration)

- Course (acute, recurrent, or chronic)

- Laterality (unilateral vs. bilateral)

The most common type of uveitis is acute anterior uveitis. According to the above classifications, uveitis specifically affects the anterior parts of the uveal tract and is characterised by a sudden onset and limited duration. The distribution of the condition is high, from 60.6% to 90.6%.(7) Most often, acute anterior uveitis is idiopathic (37.8%), which means it is not related to any illness or inflammation in the body.(7,8) However, genetic factors, trauma, diseases, and infections may trigger/cause anterior uveitis. The most common genetic relationship with acute anterior uveitis is the HLA-B27 genotype. Be aware that only 1% of patients who carry the HLA-B27 allele develop anterior uveitis.(9) The most associated conditions with anterior uveitis are seronegative arthropathies (ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter syndrome, psoriatic arthritis (no psoriasis per se), inflammatory bowel disease), juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), herpes virus, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis.

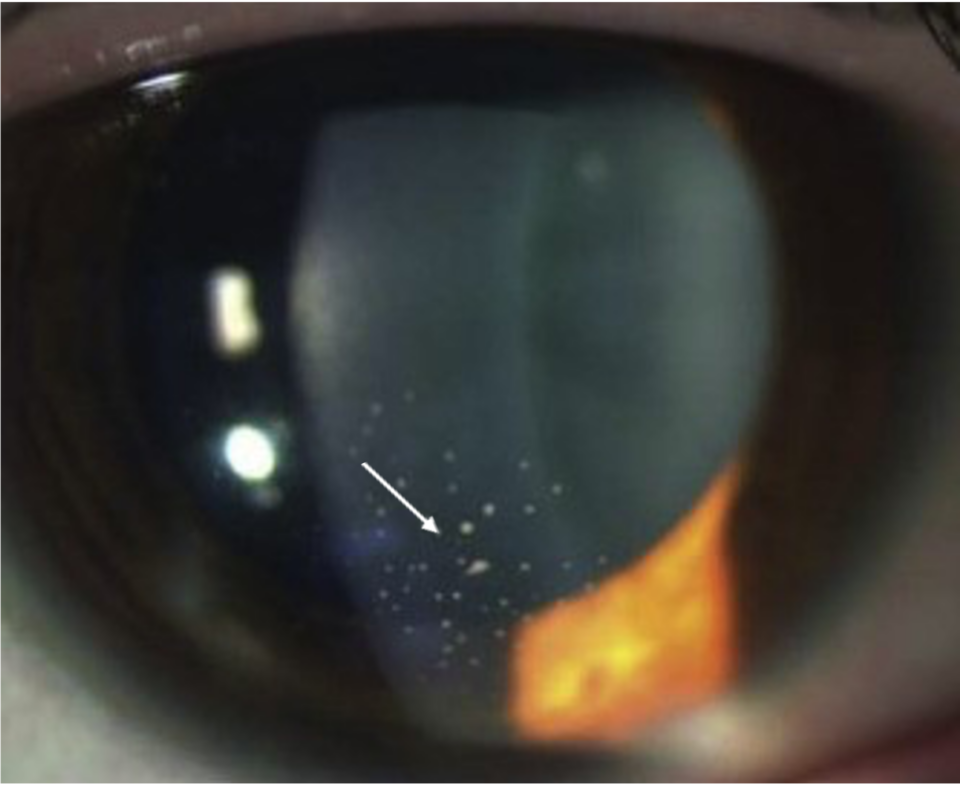

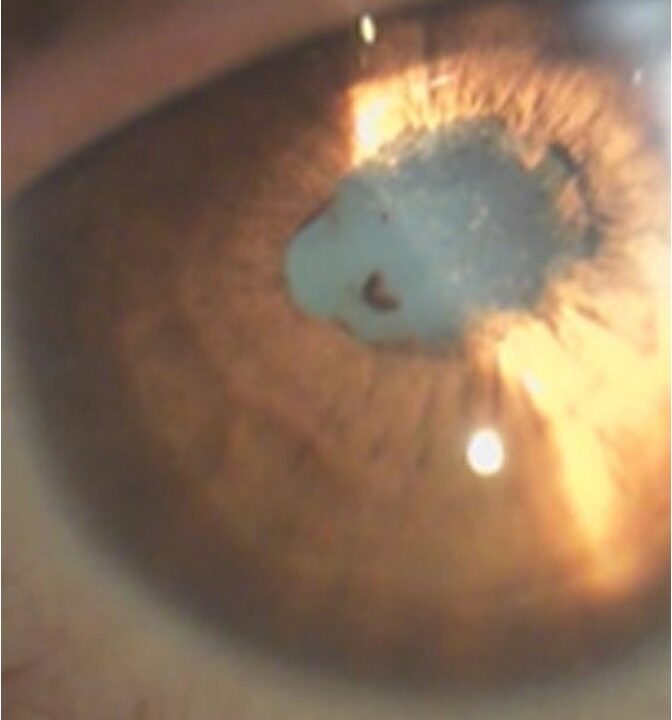

The pathomechanism of anterior uveitis is not completely clear. A leading theory is that exposure of an individual with a genetic predisposition to an infectious agent result- in cross-reactivity with ocular-specific antigens (molecular mimicry) with resultant iritis.(10) In clinical appearance, the anterior uveitis may be non-granulomatous or granulomatous. Sometimes, based on clinical appearance, potential causes may be suspected (i.e., granulomatous AAU is present in Lyme disease, Tuberculosis, Syphilis, and herpes simplex virus).(11)