In clinical practice, professionals frequently observe benign chorioretinal lesions. Benign chorioretinal lesions are characterised by their diverse appearance and origins. These lesions can potentially grow or impact vision, particularly in the foveal region or when they invade or compress the optic disc. This chapter will describe the following lesions: congenital hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE), focal scleral nodule, melanocytoma of the optical disc, and choroidal circumscribed haemangioma. One of the most often seen choroidal lesions is a benign choroidal naevus described in another chapter.

Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE)

Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE) is generally an asymptomatic congenital hamartoma in three variant forms: solitary, grouped, or multiple-pigmented fundus lesions.(1) The prevalence of CHRPE in the general optometric population has been estimated to be 1.2%.(2) Acccording to evidence the lesion is congenital.(3) The multiple and atypical appearances of CHRPE lesions strongly connect with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) – an autosomal dominant disease with numerous adenomatous polyps of the colon and rectum).(4) In such cases, CHRPE lesions are usually bilateral.(5) Ninety per cent of patients with FAP manifest with CHRPE lesions.(6,7) Most solitary and grouped CHRPE lesions are scharacterised by a monocellular layer of hypertrophied RPE cells, densely packed with large, round macromelanosomes.(8,9) The choroid, choriocapillaris, and inner retinal layers are unaffected. Compared, atypical CHRPE lesions associated with FAP show RPE hypertrophy and hyperplasia, retinal invasion, and retinal vascular changes.() These lesions may be multi-layered or involve the entire retina thickness.(10)

The focal scleral nodule

The focal scleral nodule is a yellow-white, elevated, round, non-neoplastic lesion arising from the sclera and classically located posterior to the equator.(11,12) The lesion is also known under solitary idiopathic choroiditis and unifocal helioid choroiditis. However, recent imaging revealed the scleral origin of the lesion. Some evidence suggests that lesions are most often in Caucasian females.(12) Risk factors are unknown. One theory suggests that lesion has a congenital nature.(12)

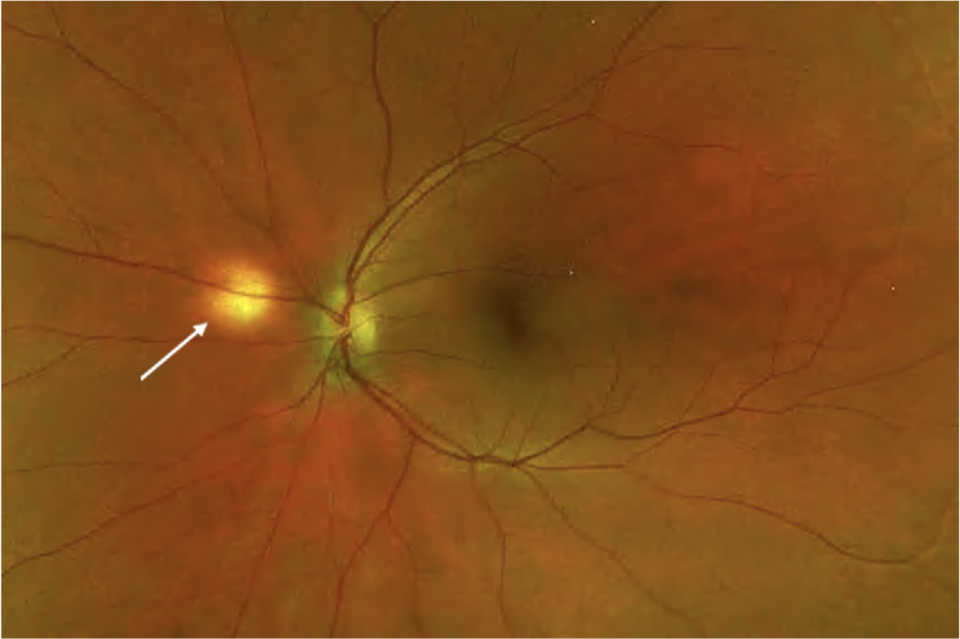

Melanocytoma of the optical disc

Melanocytoma of the optic disc is a benign melanocytic tumour, appearing with dark brown or black colour and situated at the optic disc, often with extension into the surrounding choroid, retina, and vitreous.(13)) Most melanocytomas remain relatively stable and do not cause central visual impairment. However, slight visual loss related to the tumour can occur in about 26%, usually due to mild retinal exudation and subretinal fluid.(14) There are no usually systematic associations with the lesion; it is usually unilateral. The pathogenesis of optic disk melanocytoma is unknown, but it is generally assumed to be a congenital lesion. Young children may initially have amelanotic lesions, which become clinically visible in adulthood.(14-16)

Choroidal hemangioma

Choroidal hemangioma is a benign hamartomatous disorder (hamartoma) that occurs in two distinct clinical forms: circumscribed and diffuse forms. The circumscribed form is always isolated and not syndromic, whilst the diffuse form is part of Sturge-Weber syndrome.(17) Hamartoma is a benign growth of an abnormal mixture of cells and tissues typically found in the body where the growth occurs.(18) tumours differ because hamartoma does not spread to another area. Therefore, we will focus in this chapter on circumscribed type only. It is located almost entirely at the posterior half of the fundus, within two-disc diameters from the optic disc margin. Serous subretinal fluid is standard and may be mistaken for central serous retinopathy(19) It is unilateral, and the actual incidence is unknown.