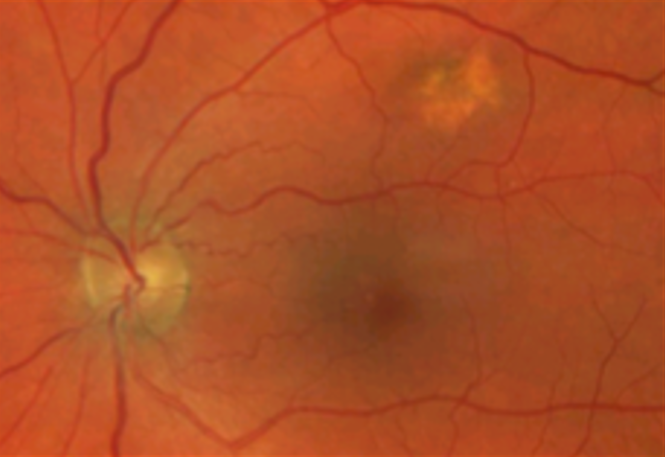

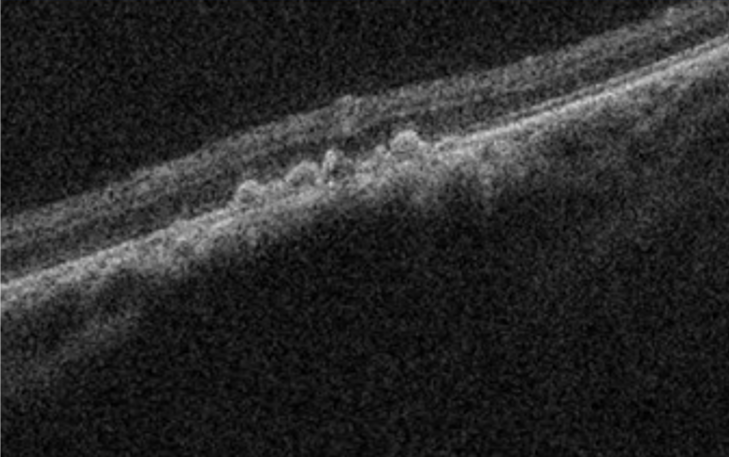

Choroidal nevi are common tumours/choroidal lesions composed of collections of benign-appearing uveal melanocytes called nevus cells.(1,2) In most cases, nevi represent benign lesions that require no treatment or additional workup. Due to the risk of transforming into a choroidal melanoma, those lesions require regular monitoring and being familiar with suspected features is crucial.

Greenstein et al. found an overall prevalence of 2.1% for choroidal nevi in a mixed population, with the highest prevalence in Caucasians (4.1%).(3) Histological findings have demonstrated that the prevalence of choroidal nevi may be higher than what is observed clinically.(4)

Thirty-one per cent of nevi will grow over time (years to decades) without malignant transformation. -According to Shields et al., the transformation of choroidal nevi is generally rare, occurring at a rate of 1 in 8,845 nevi cases per year.(5) Fair skin, the ability to tan, and light eye colour are statistically important risk factors – of choroidal melanoma transformation (6)