Uveitis is an inflammation of the uveal tract and can be divided into anterior (iris and ciliary body) and posterior components (choroid). The inflammation may affect surrounding tissue like the retina and optic nerve.(1) Uveitis – particularly posterior uveitis –is a common cause of preventable blindness, and is thus deemed a sight-threatening condition. It is responsible for between 10% to 15% of all cases of blindness and 30,000 new cases of legal blindness annually in the United States.(2)(3) In Western countries, uveitis affects 200 per 100,000 people.(4) More than 35% of patients who develop the condition suffer severe visual impairment.(4,5)

There are four types of uveitis, classified by anatomical location:

| Type of uveitis | Primary location |

| Anterior | Iris, ciliary body, or both |

| Intermediate uveitis | Vitreous |

| Posterior uveitis | Choroid |

| Panuveitis | The entire uveal tract and vitreous |

Then, uveitis is further classified based on the following characteristics:(6)

- Onset (sudden versus insidious)

- Duration (limited, less than 3 months; persistent, more than 3 months)

- Course (acute, recurrent, or chronic)

- Laterality (unilateral versus Bilateral)

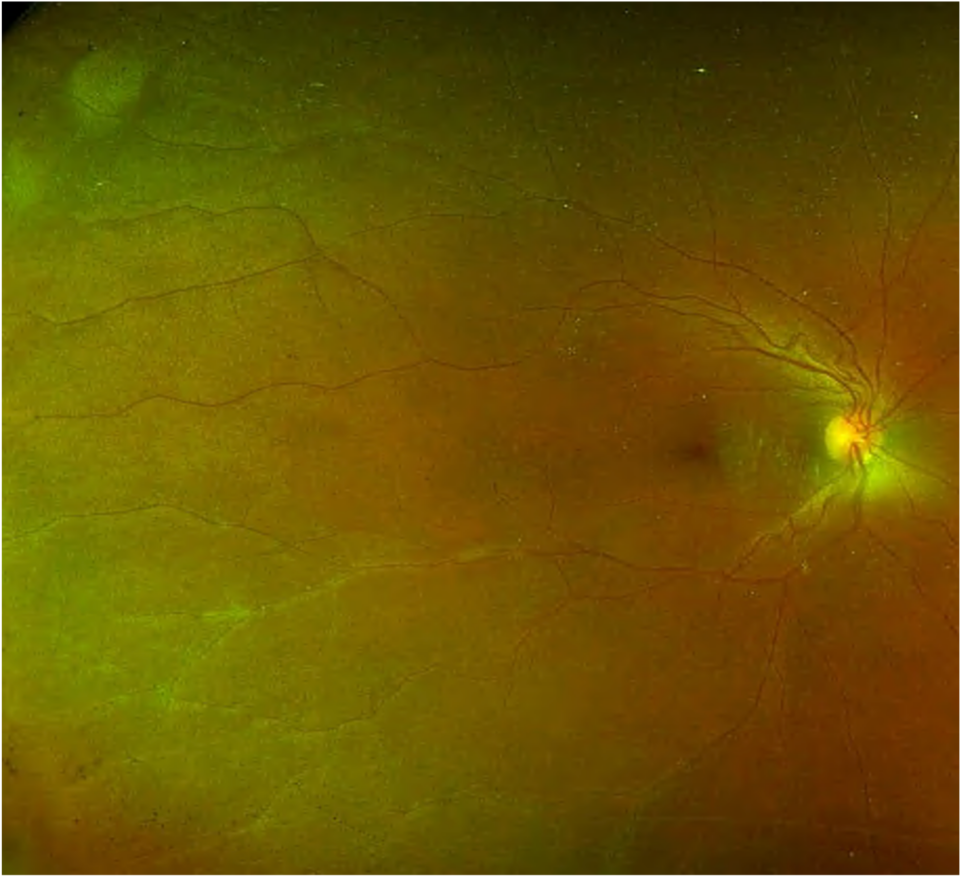

Intermediate uveitis is an inflammation of the vitreous and peripheral retina.(7) It is a chronic, relapsing disease with insidious onset.(8) Patients with intermediate uveitis may have changes in the peripheral retina (peripheral vasculitis) and/or macular oedema. Those features do not change the classification of uveitis (as agreed in the SUN working group).(7) In literature, we use different terms for the same or similar clinical features: intermediate uveitis (IU), pars planitis, chronic cyclitis, peripheral uveitis, vitritis, cyclochorioretinitis, chronic posterior cyclitis, and peripheral uveoretinitis.9 However, we use the term pars planitis when clinically in the presence of snow banks/balls without infectious or systemic cause (SUN classification). We use the term intermediate uveitis when there is presence of infectious or systemic causes.(7)

The percentage of intermediate uveitis varies depending on geographic location. In Western countries, it has been reported in 1.4-22% of all uveitis cases with a prevalence of 5.9/100,000.(9-14) In India, intermediate uveitis is present in 9.5-17.4%.(15-17) Intermediate uveitis accounts for 10 to 12% of all uveitis in children.(18) The idiopathic (unknown cause – termed as pars planitis) form of intermediate uveitis is present in 70% of cases.(19) Other causes may be infectious (tuberculosis, leprosy, Lyme’s disease, syphilis, Toxocara, Whipple’s disease) and non-infectious (sarcoidosis, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, lymphoma, tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome (TINU)).(19,20) Be aware that about 3 to 27% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) develop intermediate uveitis/pars planitis, and 7.8 to 14.8% of patients with intermediate uveitis/pars planitis develop MS.(21-23)

Intermediate uveitis typically affects people between 15-40 years. It is bilateral but asymmetrical. The incidence is equal in both men and women.

The condition is initiated by an unknown antigen or may be an autoimmune response. It is mediated by CD+4 T lymphocytes.(24,25) There is also an association with HLA genotypes (HLA-DR, B8, and B51), the most significant being HLA-DR which occurs in 67 to 72% of patients.(26,27)