Ectatic corneal disease (ECD) comprises a group of disorders characterised by progressive thinning and subsequent bulging of the corneal structure.(1,2) There are different phenotypes described in the literature: keratoconus (KC), keratoglobus (KG), and pellucid marginal degeneration (PMD).(1) Furthermore, progressive iatrogenic corneal ectasia has been reported after different refractive laser procedures and has been grouped within the ectatic corneal disease.(3,4) Throughout time, various names for the above-named conditions were used. In 2015, the Global consensus published recommendations for diagnosing and managing corneal ectatic diseases.(5)

Keratoconus (KC)

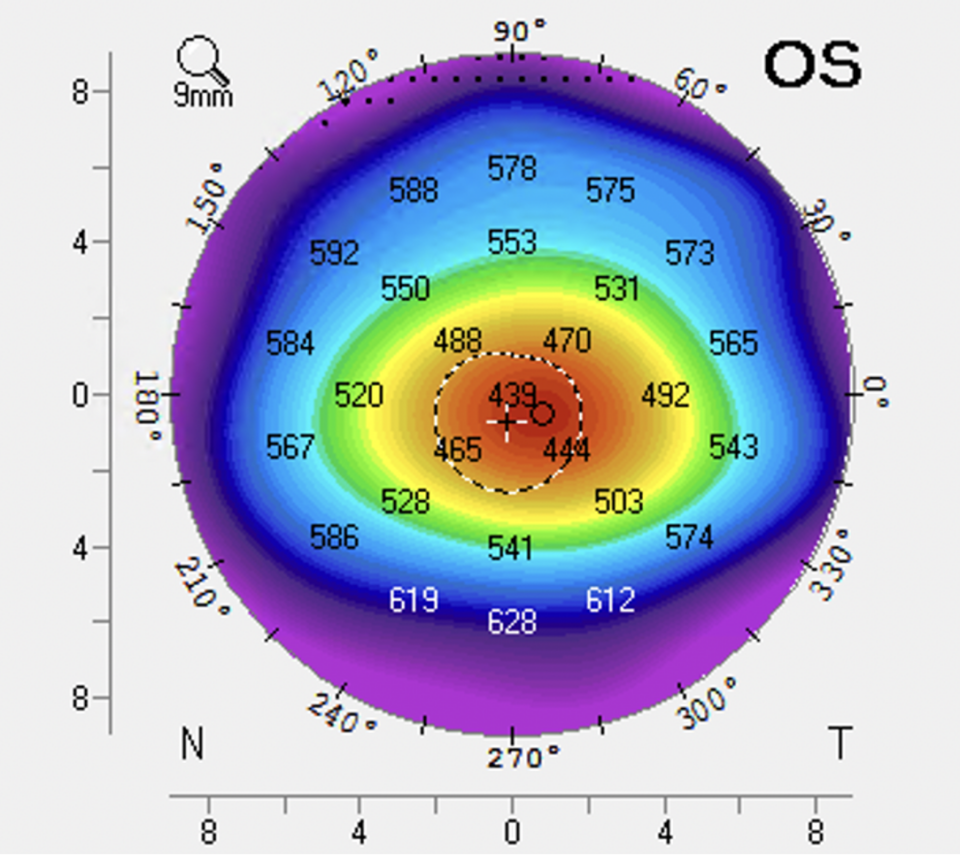

Keratoconus is a bilateral, typically asymmetrical, corneal disorder where the central or paracentral cornea undergoes progressive thinning and steeping, causing irregular astigmatism and blurred vision.(2,6) The aetiology of the disease is unknown. However, it is associated with several conditions like atopy, Down’s Syndrome, Leber’s congenital amaurosis, and Brittle cornea syndrome/Ehler’s Danlos/connective disorders. The reported prevalence is 1 in 700.(7) There are some risk factors associated with keratoconus: eye rubbing (atopy and vernal keratoconjunctivitis), Down’s Syndrome, sleep apnoea, connective tissue disorders, floppy eyelid syndrome, positive family history, and retinitis pigmentosa.(8) Signs of keratoconus, depending on its severity, are breaks in Bowman’s membrane, collagen disorganisation, scaring, and corneal thinning.

Keratoglobus (KG)

Keratoglobus is characterised by a generalised thinning and globular protrusion of the cornea, which results in irregular corneal topography with increased corneal fragility due to extreme thinning.(9) There are two major forms, congenital and acquired form. The congenital one is associated with blue sclera syndrome, Leber congenital amaurosis, and Brittle cornea syndrome (previously described as Ehler-Danlos type VIB).(18) The acquired form evolves from keratoconus and Pellucid Marginal Degeneration (PMD), and is associated with vernal keratoconjunctivitis, dysthyroid orbitopathy, and chronic marginal blepharitis.(10) The aetiology is unknown, and risk factors are not identified. There is the presence of diffuse corneal thinning and focal breaks of Bowman’s membrane, which are most severe in the peripheral cornea.

Pellucid Marginal Degeneration (PMD)

Pellucid Marginal Degeneration (PMD) is a non-inflammatory, nonhereditary cause of corneal ectasia with bilateral, clear, inferior (typically 4 o’clock to 8 o’clock), peripheral corneal thinning. It is characterised by a crescent-shaped band of inferior corneal thinning approaching 20% of normal thickness that is 1 to 2 mm in height, 6 to 8 mm in horizontal extent, and 1 to 2 mm from the limbus. There is no associated inflammation, and the central cornea is of normal thickness.(8,11) Generally, it is rare but the second most common corneal ectasia. Ten per cent of PMD cases are associated with keratoconus, and 13% are associated with keratoglobus.(8) Histological findings are similar to those found in keratoconus.

Ectasia

Ectasia is a rare complication of corneal refractive surgery, and occurs in just 0.04% to 0.6% of procedures.(12) A large study found that 96% of ectasia cases occurred due to Laser-Assisted In Situ Keratomileusis (LASIK) and 4% due to Photorefractive keratectomy (PRK).(13) There are also cases of ectasia reported after the Small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) procedure.(14) It results from a loss of biomechanical integrity of the cornea with subsequent thinning and steepening of the tissue. Screening for cases at higher risk for ectasia progression became a significant concern in the preoperative phase of elective refractive procedures.(15)