Uveitis is an inflammation of the uveal tract, and is divided into anterior (iris and ciliary body) and posterior components (choroid). The inflammation may affect surrounding tissue like the retina and optic nerve.(1) Uveitis – particularly posterior uveitis – is a common cause of preventable blindness, and is thus deemed a sight-threatening condition. It is responsible for 10% to 15% of all cases of blindness and 30,000 new cases of legal blindness annually in the United States.(2,3) In Western countries, uveitis affects 200 per 100,000 people.(4)4 More than 35% of patients who develop the condition suffer severe visual impairment.(4,5)

There are four types of uveitis, classified by anatomical location:

| Type of uveitis | Primary location |

| Anterior | Iris, ciliary body, or both |

| Intermediate uveitis | Vitreous |

| Posterior uveitis | Choroid |

| Panuveitis | The entire uveal tract and vitreous |

Then, uveitis is further classified based on the following characteristics:(6)

- Onset (sudden versus Insidious)

- Duration (limited, less than 3 months; persistent, more than 3 months)

- Course (acute, recurrent, or chronic)

- Laterality (unilateral versus Bilateral)

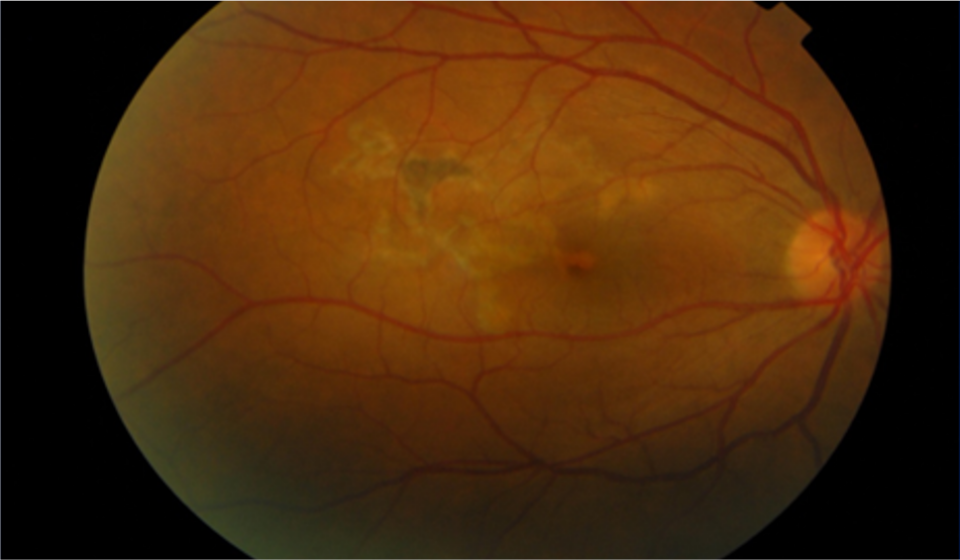

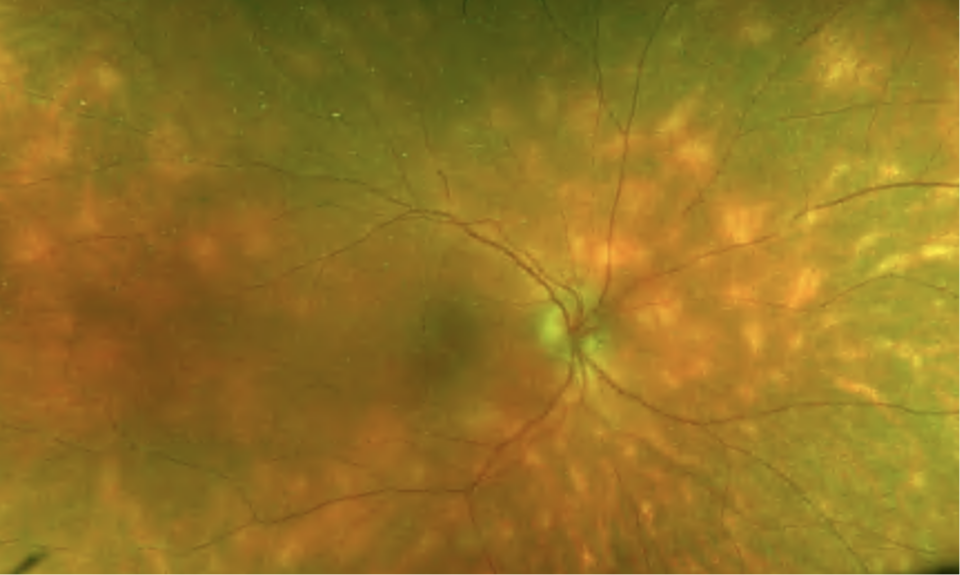

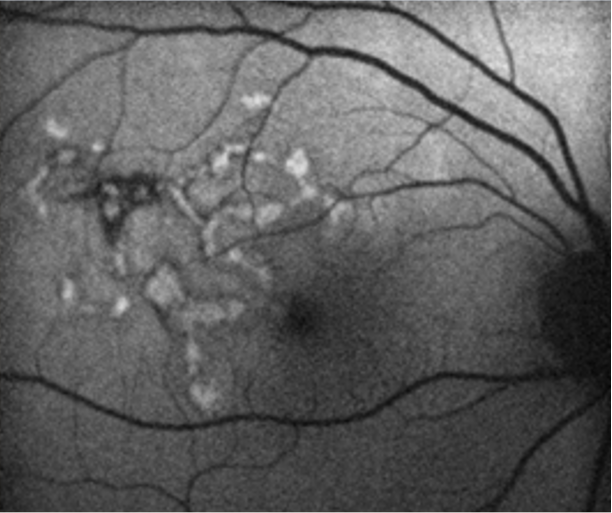

The primary site of inflammation in posterior uveitis is the choroid. It can involve adjacent structures such as the retina, vitreous, optic nerve head, and retinal vessels.(7) Posterior uveitis can be classified based on the cause or the type of lesions. Like in other forms of uveitis, its causes can be infectious (toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis, tuberculosis, syphilis, bartonella, herpes simplex virus, herpes zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, HIV) or non-infectious. Non-infectious types of posterior uveitis may be clinically presented in different ways. Diagnosis is made depending on clinical features and the results of diagnostic testing (i.e., white-dot syndromes, diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis, sarcoidosis, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, sympathetic ophthalmia, serpiginous chorioretinitis, etc.).

The term panuveitis is used when anterior, intermediate, and posterior uveal structures are involved.(8) The causes related to panuveitis are infectious, inflammatory, neoplastic, or traumatic. When neoplasia (retinoblastoma, iris melanoma, and systemic haematological malignancies such as leukaemia and lymphoma) causes panuveitis, it is known under the term “masquerade syndrome”.