The vitreous is a clear gel that fills the space between the lens, ciliary body anteriorly, and retina posteriorly.(1) It comprises approximately 80% of the volume of the eye, and consists of approximately 98% water and 2% proteins, and an extracellular matrix. Collagen is the major structural protein (type II 75% and type IX 15%).(1,2)

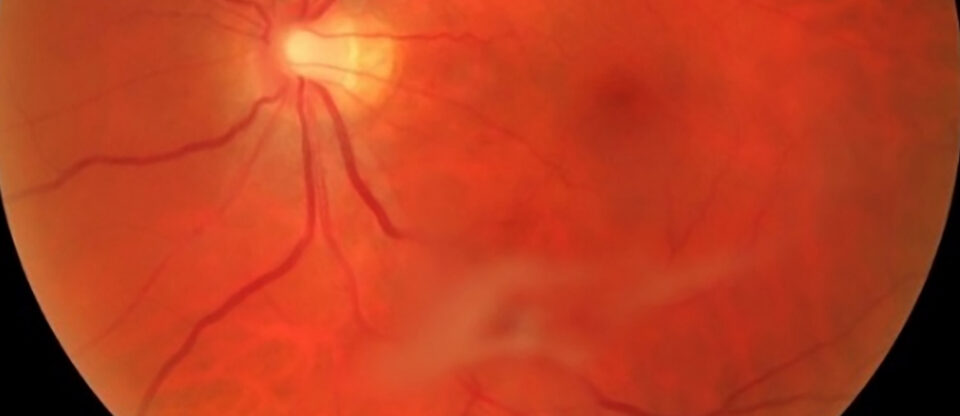

The strongest attachment points of the vitreous are at the optic nerve, macula, ora serrata, and major retinal blood vessels.(3) The equatorial and posterior vitreous interface consists of the posterior vitreous cortex, internal limiting membrane (ILM), and the intervening extracellular matrix. The intervening extracellular matrix is a macromolecular complex that glues the ILM and posterior cortex. It is composed of fibronectin, laminin, chondroitin sulfate, and other structures of the extracellular matrix.(1)

Posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) is a separation between the neurosensory retina and the posterior vitreous cortex.(4) The initial event is liquefaction and syneresis of the central vitreous (it becomes liquid and shrinks due to age).(1,2) A rupture develops in the posterior hyaloid (or vitreous cortex) through which liquefied vitreous flows into the retrovitreous space, separating the posterior hyaloid from the retina.

The prevalence of PVD increases with age and the eye’s axial length. The general onset of the event is between the ages of 60-80, with no difference between men and women. Risk factors for developing PVD earlier in life are high myopia, blunt ocular trauma, inflammation of the eye, and previous eye surgery, particularly cataract surgery.