The vitreous is a clear gel that fills the space between the lens, ciliary body anteriorly, and retina posteriorly.(1) The vitreous comprises approximately 80% of the volume of the eye. It comprises approximately 98% water and 2% proteins, and an extracellular matrix. Collagen is the major structural protein (type II 75% and type IX 15%).(1,2)

The strongest attachment points of the vitreous are at the optic nerve, macula, ora serrata, and major retinal blood vessels.(3) The equatorial and posterior vitreous interface consists of the posterior vitreous cortex, internal limiting membrane (ILM), and the intervening extracellular matrix (ECM). The intervening extracellular matrix is a macromolecular complex that glues the ILM and posterior cortex. It is composed of fibronectin, laminin, chondroitin sulfate, and other structures of the extracellular matrix.(1) The vitreoretinal separation is a normal aging process that starts as the liquefaction of the vitreous gel. Eventually, it ends as a posterior vitreous detachment.(4) The posterior vitreous detachment in terms of vitreoretinal surface appearance means that the posterior cortical vitreous is completely detached from the internal limiting membrane.

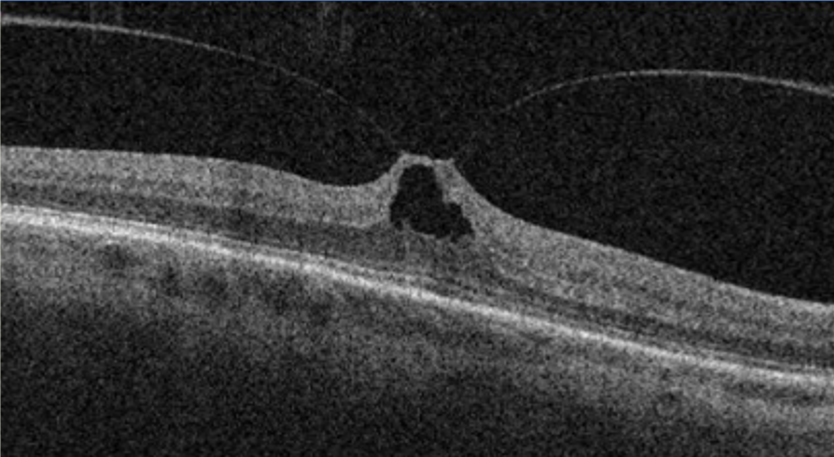

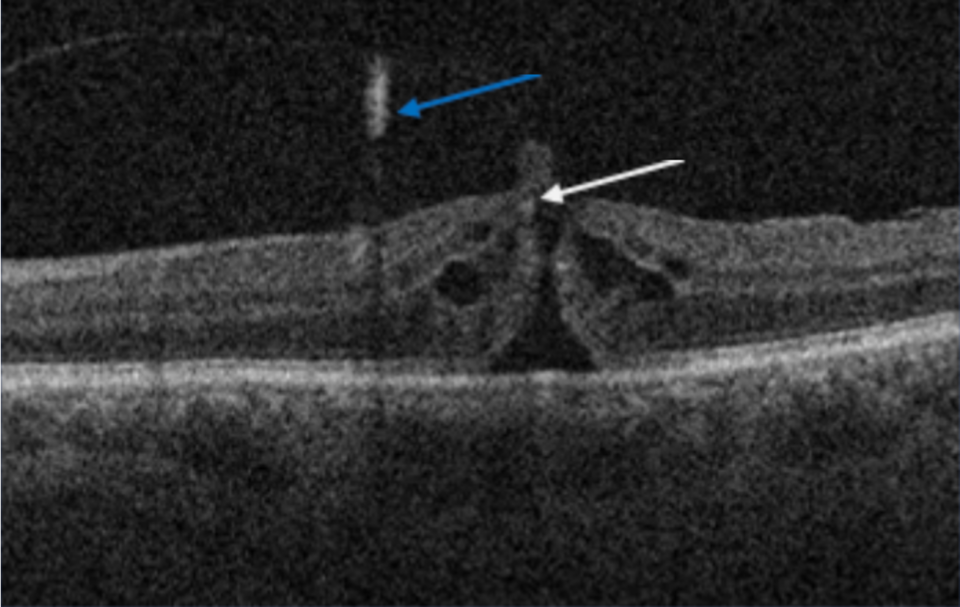

There are situations when the separation of the posterior vitreous cortex from the ILM is anomalous, either due to abnormal adhesion or when the liquefaction is faster than the separation of the posterior vitreous cortex.(5) Various conditions may develop secondary to anomalous vitreoretinal interface, such as vitreomacular adhesion, vitreomacular traction, epiretinal membrane, full thickness macular hole, and lamellar macular hole.(5,6) The early recognition and classification of those changes have been significantly improved with the OCT.