Making the subjective objective

Michael Mrochen & Svein Tindlund

Introduction

As an optometrist, do you really understand the visual needs of your patients? From experience, we know that’s not an easy task. There’s no standard or objective way to define that for a patient – it’s usually based on subjectivity and guesswork. So, how do we make the subjective objective? That’s what Svein talks about with Michael Mrochen, an entrepreneur in the ophthalmic and vision care industries and one of the persons behind Vivior, a smart device that measures data on a patient’s visual needs and translates this data into the right optical solution.

- Q1 What's your background?

- Q2 How do ophthalmologists get to know the advanced vision needs of their patients?

- Q3 Are our patients able to give us the right information about vision needs?

- Q4 Could you tell us about your innovation?

- Q5 How does this work in practice for our patients in optometry clinics?

- Q6 How can we access and use the collected data?

- Q7 Can you show me how the system looks like?

- Q8 Do you also have charts that are targeted towards the patient?

- Q9 You’re recording direction and colour temperature to estimate if a person is inside, outside or in front of a computer?

- Q10 What’s the feedback from patients and clinicians?

- Q11 How do you see Vivior in an e-health perspective?

- Q12 Where can we learn more about your work?

It’s a pleasure to spend some time with you, Michael! You’re probably one of the few non-ophthalmologists who have been listed multiple times on The Ophthalmologist’s Power List of most influential people in the industry. Tell us a bit about your background and why you became so fond of eye care?

A great pleasure to meet you again as well, Svein! Quite early in the nineties, I got the opportunity to get into optics, lasers and optical design, as I worked for a company that’s now called Carl Zeiss Meditec. I got very excited about combining the world of technology with vision and vision improvement. I also had the joy of working with one of the leaders in ophthalmology, Theo Seiler. He could fantastically bridge the world of ophthalmology with innovations and technology. These experiences have made me enthusiastic about ophthalmology and vision care! I now have the pleasure to bring technology to patients who want to see better and maintain their vision.

That brings us to my next question, about patients and their needs. To really understand their visual needs is not an easy task. As an optometrist, I must admit that I’m probably often closer to guessing than knowing for sure what my patients need. Particularly for the advanced vision needs with modern work life and several distances and angles. Is it the same for ophthalmologists? When it comes to modern cataract surgery with multifocal IOL’s you need to map the vision needs in the same way, right?

Yes, absolutely. That’s precisely why we came up with the idea of making a device that makes it possible to map visual habits and translate needs into hard data. I had the opportunity to join cataract surgeons worldwide. They work with the term ‘target refraction’, meaning the refraction they want to achieve after cataract surgery. I learned that there’s no standard way of how we define that for a patient. It usually comes down to a conversation with the patient, and then it’s pure guesswork.

If you take another example and look at how clinicians evaluate the suitability of multifocal intraocular lenses to give patients more independence of spectacles, you’ll get the same answer. There’s no objective way of how clinicians can evaluate vision needs. It all comes down to – in the best case – a structured questionnaire. But in reality, it’s often just a conversation – sometimes structured, sometimes unstructured.

Of course, we want to trust our patients on what they tell us, but the question is: are they able to give us the information that we need?

Those who’ve been involved in marketing for longer may recognise that we’ve completely moved away from asking consumers. Marketers and consumer researchers learned that it’s more important to understand our consumers’ behaviours. And that can’t be done by doing questionnaires because our self-reported information usually leads to biased feedback. It’s challenging to get objective information just by asking people – so this also goes for patients.

And still, that’s exactly what we optometrists are doing: we ask questions. And I understand that. So, another example: when performing surgery, it’s – of course – essential to get it right in the first attempt. But I think getting it right is also crucial for optometrists because we don’t know if a dissatisfied customer comes back. It’s hard to measure, and we might lose them if we don’t provide them with the right pair of glasses. You saw this problem many years ago and chose to do something about it in a way that no one had done before. Could you tell us about your innovation, Michael?

You address an excellent point there, Svein. When I talk to clinicians, they tell me they often don’t get the correct information from patients: how much time they spend reading, watching their smartphone, etc. There’s sometimes a complete miscommunication between the patient and the clinician.

So, the question we asked ourselves is this: is there a way to make this subjective information objective? What’s the information a clinician needs, either an optometrist for fitting spectacles or contact lenses or a surgeon for choosing the right intraocular lens? First of all, you need to get information and data on which distances the patient needs to have clear vision. We decided to measure the distance, that can be easily converted into diopters, by means of a laser radar device (called LIDAR). The second thing to know is, what are the usual light conditions? For example, does the patient usually spend more time outside, or do they drive a lot at night? And thirdly, we also want to understand the activities associated with their vision. For certain activities, you might need different vision correction or other vision needs. And some activities might be more important for one patient than for another.

We approached it like this: we took all this necessary information and designed a small wearable sensor that can be either clipped on glasses or put on a special head mount if you don’t wear glasses. This device records the information during multiple days: distance, light conditions, as well as neck and body motions and position.

And how does this work in practice for our patients in optometry clinics?

The optometrist gives the device to the patient, who wears it for a certain period and returns to the clinic. Then the optometrist will make sure to save the data into a cloud system. With this gathered data, we can give correct information about the vision needs of that patient.

How does that work? It’s a small device that you can attach very simply to any glass frame – one of the main challenges during the development was to ensure the fit to all frames! It’s very lightweight, less than eight grams, and after wearing it for some time, you don’t even realise you have an additional device on your frame. What it does, is measuring the distance every second. When we do that over multiple hours, you can imagine how many data points you get. Secondly, the device measures the body motion and the motions of the head. This is done in the same way as the laser scanning the eye in OCT technology: we’re using your head and body as a scanner. If you’re sitting behind your laptop, we can measure the distance between your eyes/glasses and the laptop, we can see the light conditions. And we can translate that to a proper optical correction.

Okay, so the patient comes back to the optometrist after using the device for a day or three. How will I, as an optometrist, then access and use the data?

First of all, the patient must be motivated to solve their vision problem – and that’s usually the case as they’ve been actively involved and are part of the experience while using the device. In the store, you can connect the device with a USB cable to a computer and download the data to the cloud within a few seconds. Then, the optometrist can enter the cloud system, where you can find the statistics around the data. Plus, the system includes the available optical solutions you provide in your store, so you can include that in your advice to the patient. You can use all this structured information to make an objective decision for your patient.

Any chance you can show me how the system looks like?

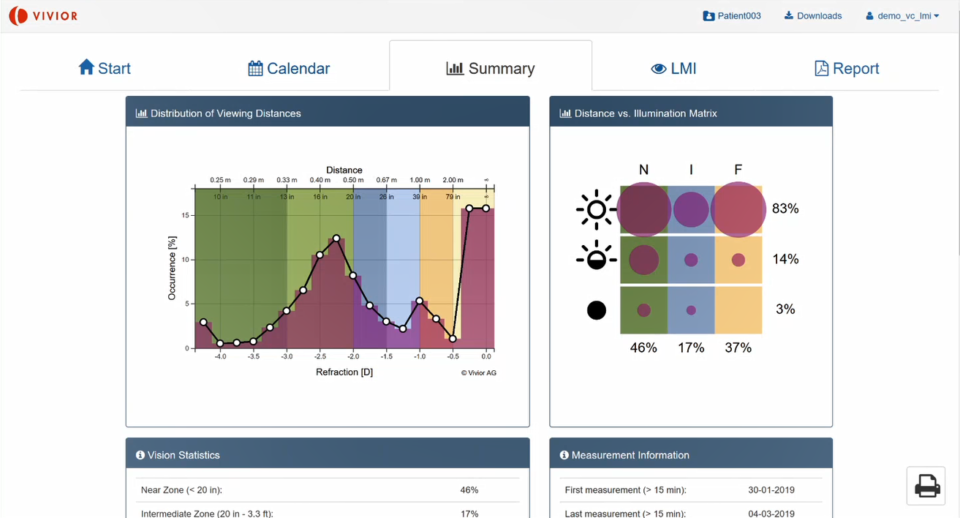

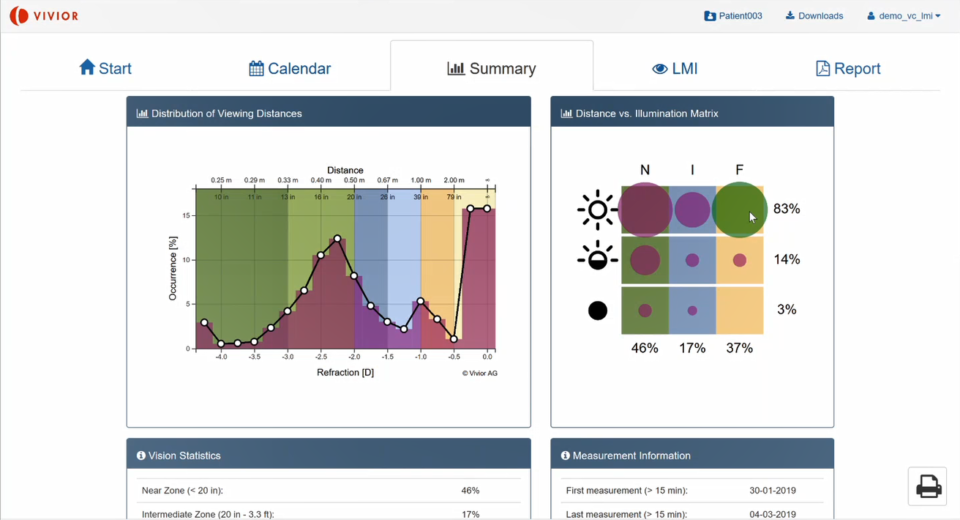

Sure! This is the summary overview (image below) where you can select the patient. The graph on the left shows the refraction – the distance – and the occurrence. You can see how the patient uses his eyes at different distances. This patient spends a lot of time in about 2.5 dioptres – behind a computer or laptop – and much time looking at far distances. We would call this patient a binocular distance patient (mainly far and near, less intermediate).

Secondly, we can stratify the light conditions – in this overview on the right. This patient spends a lot of time in bright light – especially at near and far distance. He or she probably works in an office, as there wasn’t any UV light measured, so it sure was inside.

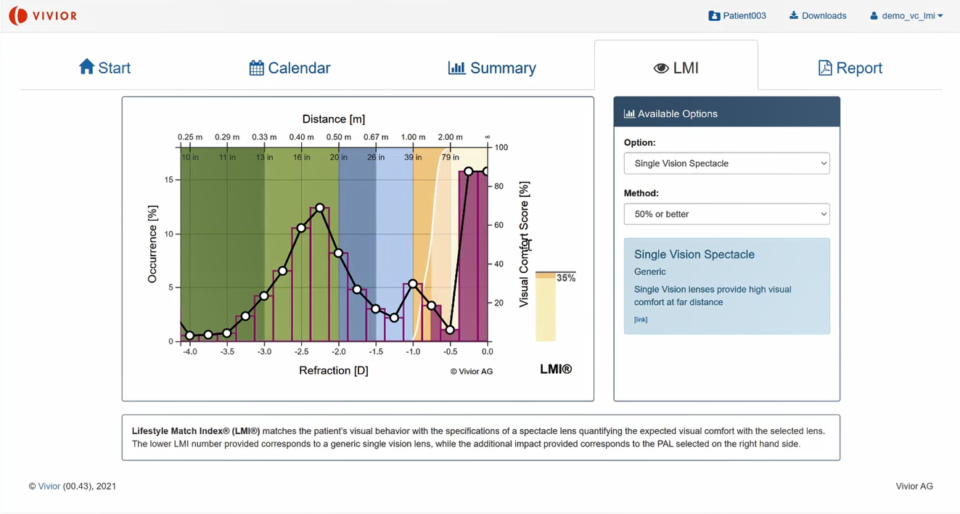

Thirdly, we can look at the solution we can provide to this early presbyopic patient. This initial example (below) shows single-vision spectacles. You can see the dioptre distribution again, and at the white line, you can see the optical coverage of a single-vision spectacle lens. You can choose alternative optical solutions and explain the benefits of all these different vision corrections compared to single-vision glasses. You can also explain the consequence of using – for example – reading glasses of 2 dioptres.

On the one hand, it’s a straightforward tool to educate the patient based on his own visual objective data. What are reasonable alternative solutions for single-vision glasses? And on the other hand, it allows the optometrist to select the best possible solution for that particular patient – based on the spectacles and lenses he has available in the store.

And you also have charts that are targeted towards the patient, right?

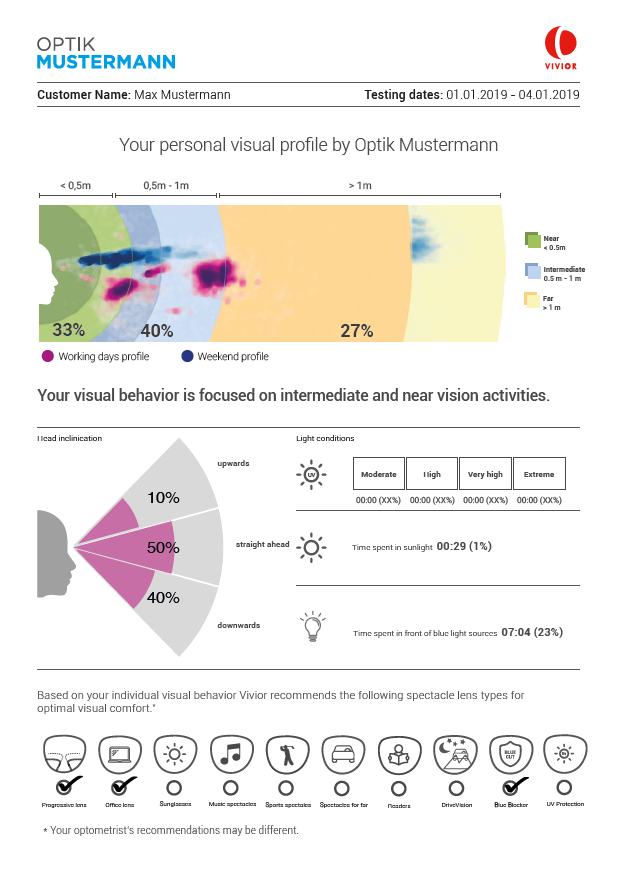

Yes, finally, we provide a report that can be emailed or printed. This report (image below) gives the patient’s data, so they understand that this isn’t just generic information but that it’s based on their behaviour and lifestyle. The system also gives automatic recommendations based on the data, for example, progression, computer glasses, blue-light filter, drive vision, reading glasses, recommendations based on sports activities – all based on what’s measured and recognised by the device.

So, you’re recording direction and colour temperature to estimate if a person is inside, outside or in front of a computer?

Yes, that’s correct. This also opens up an interesting application where we are working on: support for optometrists when it comes to progressive myopia. As we all know, our children spend more time inside and more time looking close by – which impacts the eye’s growth. We can analyse that more objectively, give recommendations, and explain to parents that their children are at risk of developing progressive myopia.

This is what I call taking the patient’s needs seriously! You boil down such a big topic into a couple of charts – really impressive that this is possible. And a real improvement from asking questions and using questionnaires. But what do the patients and clinicians say about this way of working? What’s the user feedback?

The first – and quite a frequent – concern people have is that they think it’s a camera. And, of course, they don’t want to walk around with a camera. But it’s not – there’s no camera inside. It’s a laser range finder (LIDAR), a small laser that permanently measures the distance. So just as a reassurance: we can’t see what is on the patient’s computer screen, but we can identify from the data that they’re looking at a computer or laptop.

The second piece of feedback we got is from clinicians. They say that the data from the device is actually the same as looking over the patient’s shoulder for some days and get all relevant information about distances and angles. It’s very similar to a 24-hour blood pressure measurement. Wear this device, bring back the data – and we can jointly make a decision and find a personalised vision solution.

From the optometrist’s perspective: it’s saving time, and a lot of this can be done remotely, so the patient doesn’t have to visit the store or clinic every time. Another piece of feedback is that the selection and the benefits of the lenses, especially Progressive Addition Lenses (PALs), is easier to explain to the patient. The patient understands better when there’s, for example, a higher price for higher-quality products – as they see what it does to their vision and lifestyle. The final thing we heard back is that it could help word-of-mouth publicity for optometry clinics, as we print the clinic’s name on the device.

I believe this is a true e-health solution that supports the principles of a person-centred approach to enhance the individual’s quality of life. We all know that the World Health Organisation is very clear that this is the future. How do you see Vivior in an e-health perspective?

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, working from home became more and more the standard. I’m sure we’re going to have a hybrid solution of office working and home working in the future for office employees. As an employer, it becomes more difficult and necessary to manage the health of your employees. How can I give remote support as an employer? With Vivior, we’re able to understand your vision needs, your behaviours around vision, your ergonomics – and thus, we’re able to make preventive medicine and support people with their well-being. We can give you more guidance; if you continue to look at your phone in that posture, you’ll soon have significant neck problems and most likely severe musculoskeletal disorders in five to ten years. Or you’ll have back problems because the laptop you’re working on is always standing too low. So, Vivior can give very structured information that goes beyond just vision correction. This anticipates to the growing problem of computer vision syndrome.

I think it’s very interesting that you put vision needs and visual habits into a health perspective. To conclude, where can our readers learn more about your work, Michael?

There are three publications that are interesting to share. These give more context about vision behaviour:

- The first paper is about an Italian study where they looked at the viewing distance with smartphones in people of different ages, to identify factors that could influence this distance. They measured the distance between cell phone and the eyes in more than 100 people, both presbyopic and non-presbyopic patients. Read it here.

- Secondly, an article by Arthur Cummings from Cataract Refractive Surgery Today, about Lifestyle Match Index: Helping to Choose the Best IOL. Read it here.

- And thirdly, I’d like to refer to a paper by Vivior about objective data to determine the risk factors of myopia. Download it here.