- Arterioles respond to elevated luminal pressure by vasoconstriction to reduce flow.

- Pathology develops when the increased pressure causes endothelial damage (stretching of the endothelium, breaks, and leakage of plasma into the vessel wall).

- Findings are related to the above-described pathology and represented by following

changes: vascular abnormalities, e.g. A/V ratio and dilated vessels. - Retinal haemorrhages develop when necrotic vessels bleed into either the nerve fibre layer (flame-shaped haemorrhage) or the inner retina (dot blot haemorrhage).

- Cotton wool spots are caused by ischemia to the nerve fibre layer secondary to fibrinous necrosis and luminal narrowing.

- Exudates occur due to vessel leakage.

- Papilledema is a result of both leakage and ischemia of arterioles supplying the optic disc that undergo fibrinous necrosis.

- Hypertensive retinopathy is categorised into 4 groups. Most patients with hypertension have some degree of type 1 changes, however, group 4 category hypertensive retinopathy (bilateral papillary oedema) is considered an emergency and observed in malignant hypertension.

Chapter 5: Retinal vascular diseases

Introduction

The retinal vasculature supplies the inner retina with blood. This chapter covers the following diseases of the retinal vasculature:

- Hypertensive retinopathy

- Diabetic retinopathy

- Retinal vein occlusions

- Retinal artery occlusions

Click on one of the cards below to read more about the specific eye condition.

Hypertensive retinopathy

The arteriosclerotic changes of hypertensive retinopathy are caused by chronically elevated blood pressure, defined as systolic greater than 140 mmHg and diastolic greater than 90 mmHg.

Diabetic retinopathy

Chronically high blood sugar as observed in diabetes is associated with damage to the retinal blood vessels resulting in leakage of fluid and bleeding.

Diabetic retinopathy may progress through four stages:

- Mild nonproliferative retinopathy: small areas of swelling in the retinal blood vessels (microaneurysms) occur at the earliest stage of the disease – may leak fluid

- Moderate nonproliferative retinopathy: as the disease progresses, blood vessels may swell and distort. They may also lose their ability to transport blood and may contribute to diabetic macular oedema.

- Severe nonproliferative retinopathy: many more blood vessels are blocked, depriving blood supply to areas of the retina. These areas secrete growth factors that signal the retina to start growing new blood vessels.

- Proliferative diabetic retinopathy: at this advanced stage, growth factors secreted by the retina trigger the proliferation of new blood vessels, which grow along the inside surface of the retina and into the vitreous gel. The new blood vessels are fragile that makes them more likely to leak and bleed. Accompanying scar tissue can contract and cause retinal detachment. Retinal detachment can lead to permanent vision loss.

Retinal vein occlusions

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) has a prevalence of 0.5%, making it the second most common retinal vascular disorder after diabetic retinopathy.

RVO is classified according to the anatomic level of the occlusion, with three major distinct entities:

- Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO): occlusion of the central retinal vein at the level of (or posterior to) the lamina cribrosa. (See image 5)

- Hemiretinal vein occlusion (HRVO): occlusion at the disc, involving either the superior or inferior hemiretina.

- Branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO): occlusion of a tributary vein, typically at the site of an arteriovenous crossing; thought to be caused by compression from an overlying atherosclerotic arteriole. (See image 6)

Clinically, CRVO may be divided into two major subtypes:

- Ischemic: may be identified by the characteristics: poor visual acuity; the presence of a relative afferent pupillary defect, extensive dark (deep) intraretinal haemorrhages, multiple cotton-wool spots

- Nonischemic

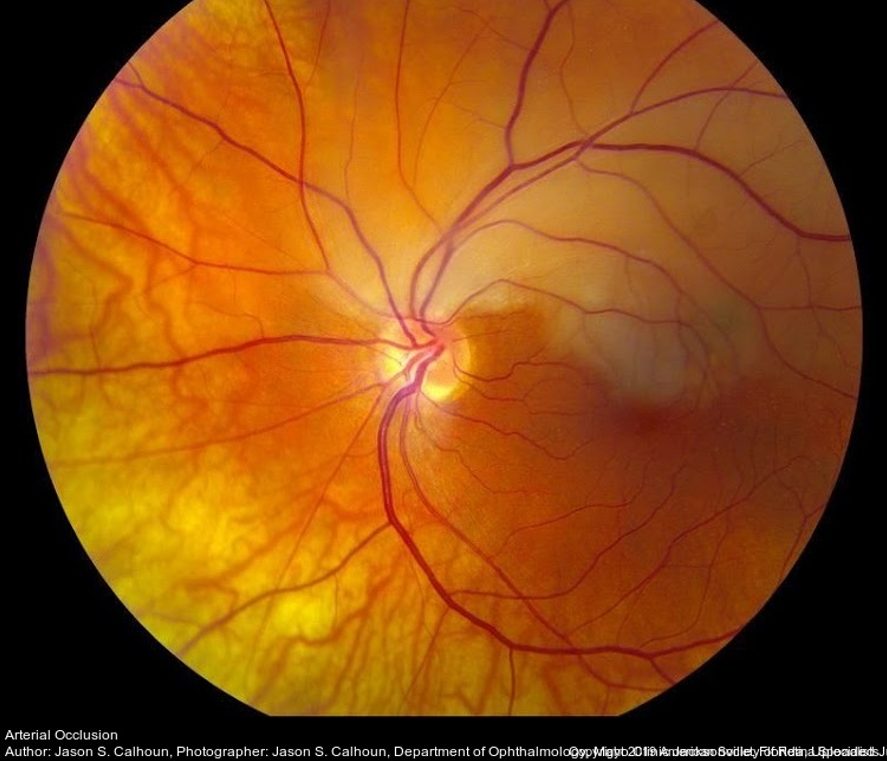

Retinal artery occlusions

Retinal artery occlusion is usually associated with sudden painless loss of vision in one eye.

The main artery supplying blood to the eye is the ophthalmic artery. When it is blocked, it produces the most damage:

-

- Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO): often results in severe loss of vision. However, about 25 % of people who develop CRAO have an extra artery called a cilioretinal artery in their

eyes. When CRAO occurs, having a cilioretinal artery can greatly lessen the chances of damage to central vision, as long as the cilioretinal artery is not affected (cherry-red spot on the

macula). (See image 7) - Branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO): an occlusion in a smaller artery may cause loss of a section of the visual field, such as vision to one side. If the affected area is not in the centre of the eye or is relatively small, a BRAO may go unnoticed with no symptoms.

- Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO): often results in severe loss of vision. However, about 25 % of people who develop CRAO have an extra artery called a cilioretinal artery in their

- Most retinal artery occlusion patients are in their 60s and are more commonly men than women. It is associated with cardio-vascular lifestyle diseases. Only 1 to 2% of cases involve both eyes.

- Retinal artery occlusion occurs due to occlusion of the retinal artery, often by an embolus (cholesterol) or thrombus (blood clot), associated with vascular disease.

- The retinal artery occlusion may be transient and last for only a few seconds or minutes if the blockage breaks up and restores blood flow to the retina, or it may be permanent. All types of new occlusions require immediate medical care!

*Referral advice

The referral advice in the atlas should be used as a general guideline. The Optometry Atlas does not establish a standard of optometric care and specific outcomes are not guaranteed. Please read the full details here.